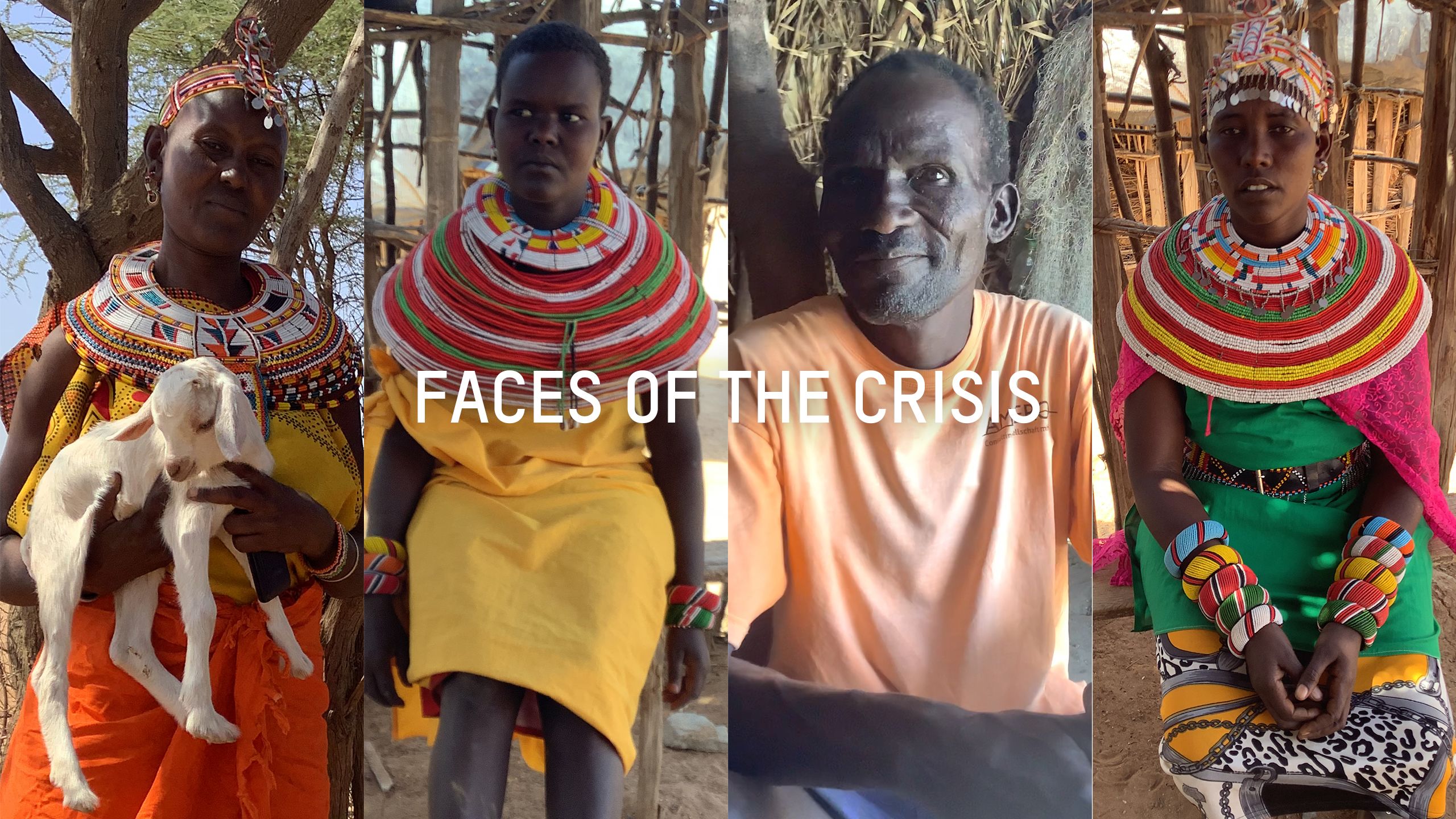

EAST AFRICA HUNGER CRISIS

One in five people in drought-stricken East Africa don't have enough safe drinking water. Failed rain is predicted to persist for a sixth consecutive season, making this the longest drought on record.

More than 31.5 million people across Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan are fighting for their lives. It’s the worst hunger crisis in living memory.

We have experienced drought for over seven years. We’ve been surviving in this harsh environment with no water.

Photo: Loliwe Phiri/Oxfam

Photo: Loliwe Phiri/Oxfam

SOMALIA

Floods, crop-devouring locusts and Covid-19 and persistent

drought since 2020 have hit hard a population already living under the strain of poverty and decades of armed conflict and insecurity. 7.7 million people will need humanitarian assistance this year.

1.8 million of the country’s children are expected to be acutely malnourished by the end of 2023.

ETHIOPIA

In the drought-affected areas, between 11.8 million people are estimated to be facing severe hunger and 13 million people are affected by drought.

The number of livestock dying from lack of food and water is staggering and increasing by the day. Millions have seen their livelihood suffer across four southern drought-affected areas. The northern regions of Ethiopia are severely affected by conflict. Levels of malnutrition in children and lactating women are alarmingly high.

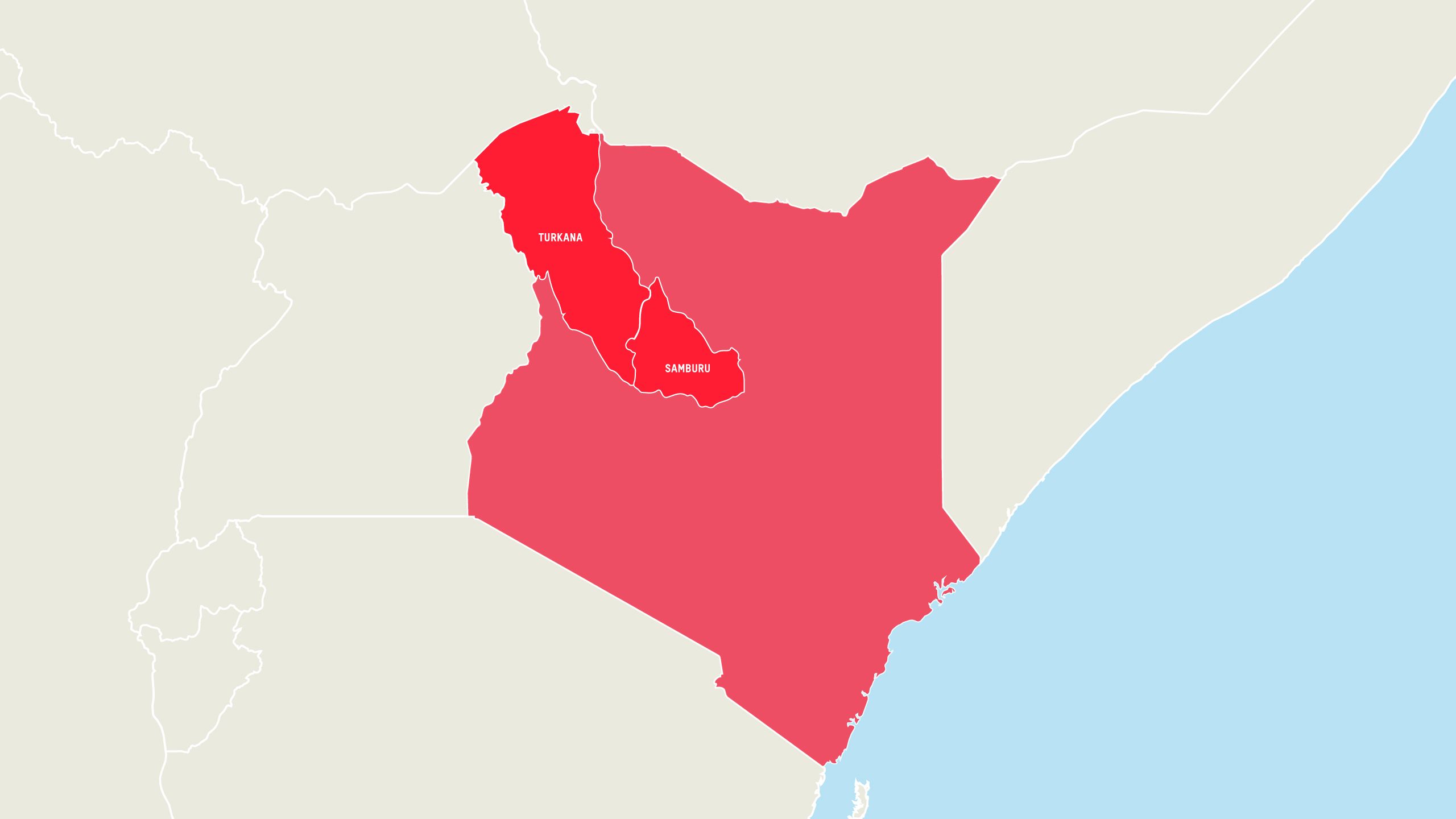

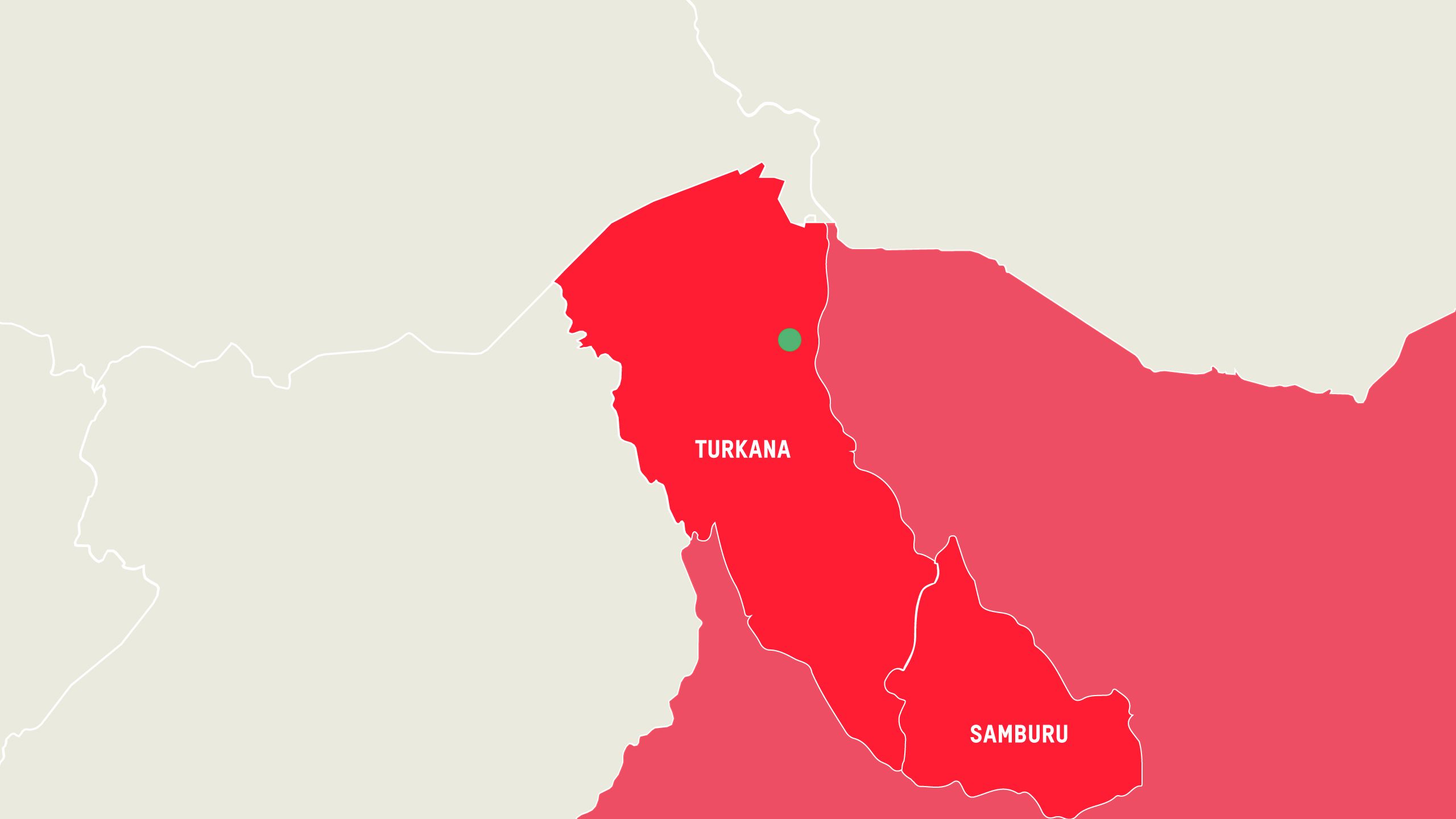

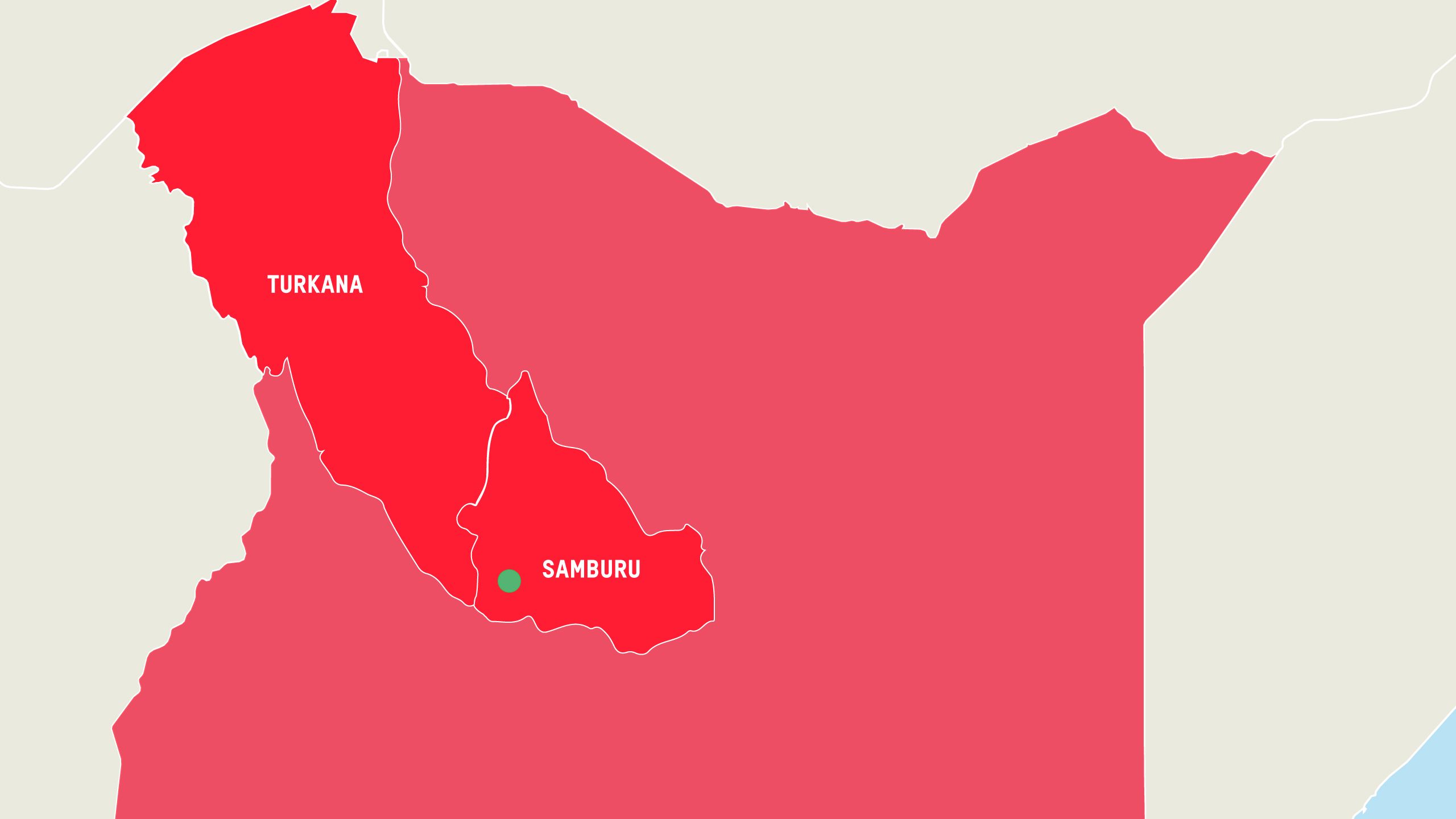

KENYA

Droughts, floods and disease outbreaks are becoming more frequent and intense, leaving little opportunity for affected communities to recover. An estimated 5.4 million people are facing severe hunger. An estimated 5 million people are in need of water assistance.

The risk of conflict over depleted resources, gender-based violence and children dropping out of school are all on the rise.

SOUTH SUDAN

Over the last five years, early seasonal rain has caused rivers to overflow and the country has experienced widespread flooding. Since the start of the

Sudan crisis in April, thousands of people fled from there to South Sudan. This is putting further strain on resources.

Approximately 6.6 million people, or over half of the country’s population are experiencing crisis levels of hunger.

90%

of Somalia is in severe drought. More than 670,000 people have been forced to leave their homes in search of food and water.

31 million

people in Kenya are experiencing extreme hunger and need humanitarian help.

9.4 million

people in Ethiopia need urgent humanitarian support due to impacts of extreme drought and conflict.

How Oxfam is Responding

Partner organisations and communities are leading the response across East Africa. By donating today you’re helping to make work like this possible:

- WASDA is offering people in Wajir County, Kenya, money digitally transferred to their mobile phones, so they can buy what they need.

- Somali Resilience Programme is offering training to help farmers adapt to a changing climate.

- ORDA Ethiopia is working in areas where people are displaced to provide clean water, showers, toilets, hygiene kits and money for essentials.

Many of our partners are small grassroots organisations. Please donate now to help them support people facing extreme hunger in their local communities.

HOW DO CASH TRANSFERS WORK?

Oxfam are providing emergency cash transfers. This is the fastest way to provide aid - by supplying families with credit at their local food store or market they can purchase.

Parents receive payments to an account connected to their local market or food store. Once a parent is added to a payment cycle, they can avail of credit. Meaning they can buy foods now. Merchants will deal with them, knowing they will have funds shortly.

We are working with the media to continue sounding the alarm. In fact, last year Oxfam Ireland travelled to Kenya with a news crew. They requested our assistance in covering this climate-induced Hunger Crisis and highlighting the solutions Oxfam is providing.

ROSE

Photo: Clare Cronin / Oxfam

Photo: Clare Cronin / Oxfam

What can one woman do in the face of the worst drought in 40 years and climate change? For single Mother of six, Rose Lekata, the answer was to buy a goat.

Rose felt some good fortune came her way when she became part of an Oxfam Ireland supported cash transfer program last December. The direct payments, little over €70 a month usually spent on food, gives people like Rose some control in desperate times.

For the pastoral people who live here, the Samburu, their livestock are their food, wealth when they have any, and way of life.

All of that is now under threat. In Kenya alone, an estimated 1½ million animals have died due to the drought that has no end in sight. The condition of remaining animals is poor and prices are back to 2017 levels.

Her original investment had led to her now being the proud owner of two goats and a week-old kid. Her animals are in outstandingly good condition as are her family and this is all down to her good management of very scare resources. Rose saw an opportunity.

Talking through an interpreter, she told us how she goes to the local market each day and collects scraps to feed her animals. She shows us a box of watermelon skin, damaged cabbage leaves and the waste that is thrown away at vegetable stalls.

She often has to ask the stall owners if she can have these pickings as everyone in this part of Kenya is under pressure as a fifth failed rainy season looms.

In the Umoja Women's Village where Rose lives, her entrepreneurial spirit and animal husbandry are celebrated. All of the women here have been the victims of domestic/gender violence and Rose puts herself at some risk in her daily outings to the market.

Lawlessness of all sorts has increased and in order to protect her assets, Rose brings her goats into her hut at night to ensure they are not stolen.

Speaking through an interpreter, her answer to her past life is this; “She had a husband. He used to beat her even though she worked very hard every day. He didn’t contribute so in the end she didn’t see the point, and she left.”

"He (the husband) wasn’t prepared to put the girls in school, and this was a source of conflict.” Four of Rose’s six children are girls and she has a three-year old grandson she looks after also. This child’s Mother, has gone to the Masi Mara in Kenya to took for a job in the tourism industry. She has been gone two months and is still job hunting.

Just like Mothers in Ireland, Rose’s main concern when we visited was getting her children back to school. They must leave at 5 a.m. and attend from 6 a.m. to 3 p.m. Her greatest wish is to see her daughters go to secondary school and she plans to sell one of her goats to pay for this. Secondary school education is not free in Kenya. Because of the remoteness of the area and for security reasons the secondary schools are also often boarding schools.

As we leave, she hopes the goat will fetch enough to cover the cost of school bedding, fees, books and uniforms. As well as the all-important food that is everyone’s main concern in East Africa these days.

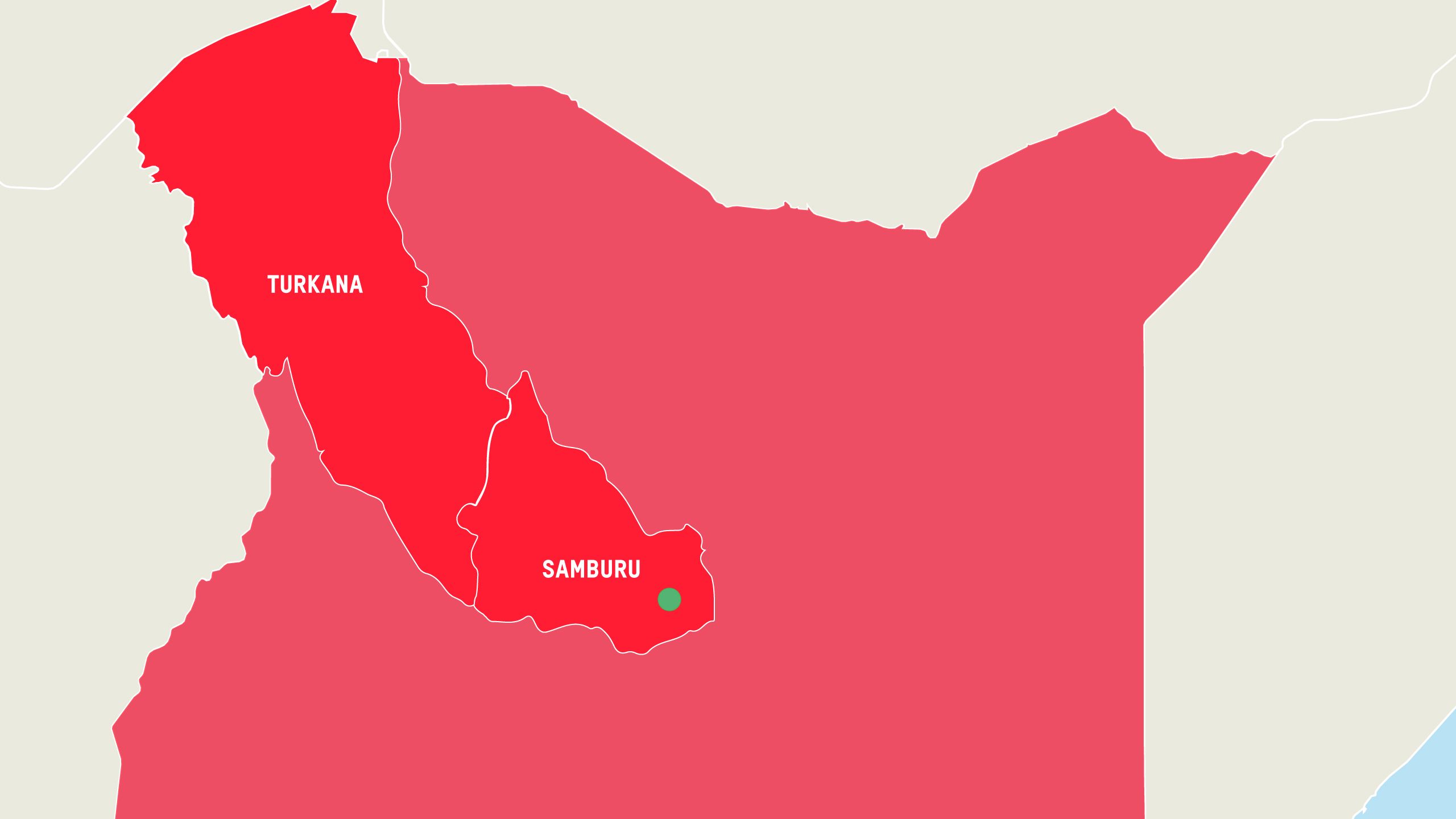

MPANISA

Officially, Mpanisa doesn’t exist. At 15, she is too young to be counted a resident at Umoja Women's Village. But not too young to be married off to a much older man as his third wife.

This unique community of survivors of gender violence counts36 residents –and Mpanisa and another 15 year old girl, officially children. The matriarch and founder of the village and the Samburu Women’s Trust is Rebecca Lolosoli, who acts as translator for Mpanisa.

They both know the Samburu tradition is to marry young but both acknowledge this drought has contributed to the nightmare that led to Mpanisa running away. She was traded for two cows by her Father. Despite the trauma, the importance of livestock stays with Mpanisa.

Her husband should have given her family five cows, she tells us, but he didn’t fulfil his promise. Mpanisa comes from a family of eight children. She is a middle child with two younger sisters and one younger brother. When asked about returning home, her meek manner hardens to a very definite no.

“The police chief brought her here two months ago,” says Rebecca, “she hardly had clothes on her back and was in a bad way.” Rebecca understands that if she were to go home to her family she would be returned to her abusive husband or married off again.

Refuge like that provided at Umoja is rare in Kenya. Rebecca says she founded it because "many women have died because of violence, they have come here to stop the death of their children and continue living."

Understanding what Mpanisa was up against the women at Umoja looked for solutions. The 36 households in the village are supported by Oxfam Ireland with direct cash payments that are worth a little over €70 a month to date. Rampant food inflation is leading to review. This basic payment is often further depleted by the Samburu tradition of mutual support and sharing.

So it was that 86-year-old Rantilei, opened her home to Mpanisa, who helps her around the house. Rantilei further shares her allowance with another 15-year-old. This girl also ran away from forced marriage and female genital mutilation. When we call, she is at school. Rebecca is looking into whether Mpanisa could or should attend education.

The hut they all share is spotlessly clean with an earthen floor. It contains no furniture just some jerry cans for water. Goat skins are used as bedding, there is one tiny stool. The one decoration is a colourful election poster from the recent Kenyan elections.

When asked if they like or support the candidate the women say no, they just wanted to have something to decorate their home. A reenforced steel door provides some peace of mind and safety. For now, this is what Mpanisa needs most.

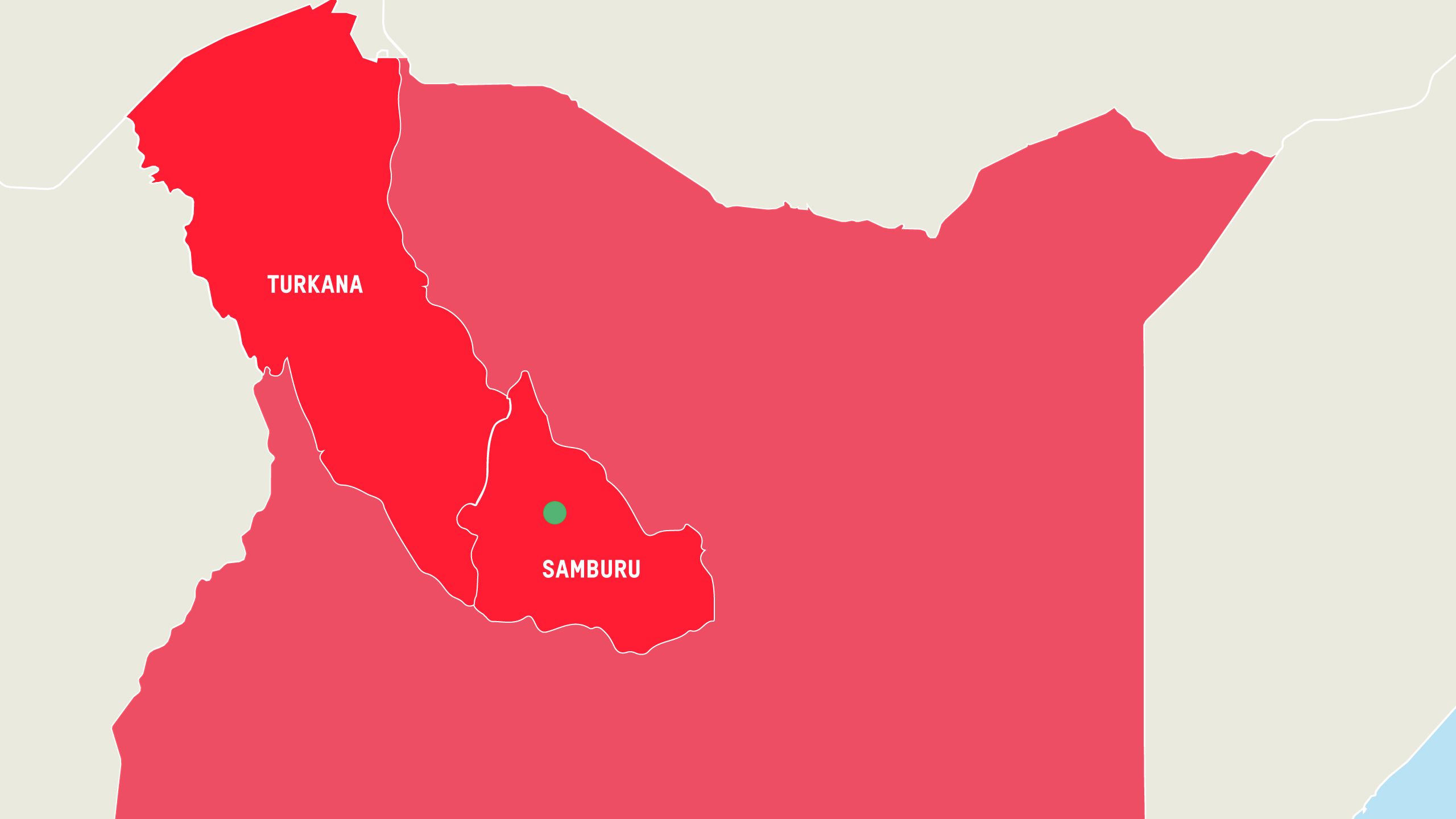

JOHN

John (Ekamais Erinyok ) who lives in the village of Narengewoi in Turkana County, Kenya.

Oxfam in Kenya’s Humanitarian Strategist, Everlyne Situma, sets the scene in this region where rains have been erratic for at least the past eight years: “You notice the emaciation of people, how they have really wasted away, no muscle left just bone. Year by year they have lost or had to sell the livestock they depend on and now they have nothing.”

When we visited John, he had just got his last monthly payment of 8,698 Kenyan Shillings. That is €72.98 for John, his wife and eight children for one month. Food inflation is rampant in Kenya, and we asked John to show us what sort of food that allows for.

The family have one meal a day consisting of one kilo of maze and one kilo of beans. John explains that many displaced people have now moved to Narengewoi to be near a place with a cash transfer system. The local custom is to share whatever food is available so that further reduces what any supported family has to eat.

In terms of food inflation, the cost of the staple, maize has gone from 90 Kenyan Shillings a kilo some months ago to 230 Kenyan Shillings a kilo now.

Oxfam Ireland is working with partners in the region to provides direct cash transfers to families in need in their home communities. 75% of the estimated 877 households in Narengewoi village are supported.

KARERI

When Kareri ran from her husband she travelled for four days and over 300 kilometres before she felt in any way safe.

She even left her six children behind as she took refuge with some distant relatives. She missed her children terribly and worried about them constantly. After a year and 3 months and following an attack in which her husband burnt her out of her new home, she went back to get her children. She ran again, this time to the sanctuary of the Umoja Women’s Village, supported by Oxfam Ireland through the Samburu Women’s Trust.

Standing in the village today, Kareri moves some of the splendid, crafted beadwork that the women make to support themselves, to display deep scars left by her husband’s attacks. She was the second of three wives and is 35 years old.

Like everyone here she has the dreadful worry of where to find enough food for her family. In addition, she has a son with a mental disability. She does her utmost to pay fees for him to attend a special school which is some distance away.

“Life is better now”, she says. “I hope the support we get here continues. This drought makes everything worse. There are escalating tensions and conflicts of all sorts and big increases in the costs of food, so I hope the support will sustain us into the future”.

In addition, Kareri abusive husband has not gone away. He came looking for her in the village and she along with her children and some of the women fled to the police. The police chief was at first sympathetic to her husband with whom he shares tribal affiliations. But the women of the Trust prevailed, and he returned home. No one is sure if he will return.

The matriarch of the village, Rebecca Lolosoli, is aware of how vulnerable the residents are. The huts are made of timber and mud. There is no secure entrance. Marauding elephants are one concern but the human threat is uppermost.

She mentions rape and burglary as she shows me one of three reenforced steel doors they have installed on the resident’s huts. They cost $300, and any spare cash goes straight to buying more.

They offer some peace of mind and security to women who badly need both.

JOIN US

Sign up to stay informed of latest news concerning Oxfam Ireland and how you can get involved

Follow us on social media